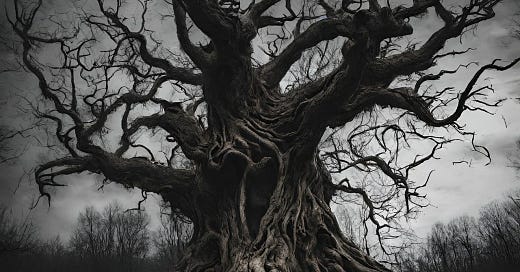

“The Fear… It calls to me…”

As we march steadily towards October 31st and the celebration of all things ghoulish, what better time to examine my favourite genre? For those who don’t know my fictional work, I’d consider myself primarily as a horror writer. Because of this, I’m often asked why I enjoy these kinds of things. Ignoring the judgement that often accompanies such questions, I actually have to say, this is one of my favourite topics surrounding the genre. If horror seemingly evokes such negative emotions, why is it enjoyed by so many?

First, and foremost, horror is undeniably entertaining - at least for a certain kind of person. The genre taps into something primal and animalistic. It reaches out and embraces the deepest part of our lizard brains. The rush we feel during particularly grotesque or intense scenes, can leave us with a sense of exhilaration and the knowledge that our own situations are much better than those of the heroes, as they step down dark gloomy stairwells towards the sound of clanking chains. Yet this answer rarely satisfies those who dislike the genre. They don’t enjoy that particular brand of emotional cocktail, so how could anyone else? Such an answer can even reinforce their belief that horror is unhealthy, or it produces psychopaths.

So, when faced with this question, I tend to lean more towards a philosophical explanation. Through horror, we get to confront evil directly. We look it in the eye. For a short while, we get to indulge in the notion that evil is as simple as a zombie rising from its grave. It’s as understandable as a shapeshifting clown living in the sewers. In those moments, we can pretend evil is easy to define, rather than being the complex and disturbing reality we face in real life. Engaging with horror allows us to condense real evil into archetypes to be analyzed in a safe space. A space where we can explore our fears and anxieties without any threat to our person or mind.

It’s like how teenagers often use horror movies as a social test. Where the act of maintaining composure determines their standing amongst their peers. In this same way, the horror story is meant to push against your own boundaries and explore the things you find taboo. Importantly it does it in a way where there are no real-life consequences. Instead, we get to eat popcorn, crack jokes, and cover our faces when things get spooky. This activity is a form of what psychologists call emotional regulation. It grants us a sense of control over our experiences and feelings of fear.

So, when I get asked why I do what I do, or how I can like the things that I like, the answer is simple:

In those moments of darkness, when it’s just me and an unspeakable abomination on the TV screen, I can confront the things I usually suppress. I can use horror as a workshop to safely explore what goes bump in my own personal night.

I’m able to make peace with the darkness in our world, and the darkness inside myself.

“The Blood That Feeds These Wicked Roots” is the first part in a four part series where I’ll be examining the history of the genre. Over the coming days, we’ll chart the evolution of scary stories from classical antiquity to the Medieval era, through the Victorian period, and into the late 19th century. Ultimately, we will arrive at the present day; in horror boom we’re currently experiencing. By understanding what has fed the roots of this fascinating genre, we can illuminate our own fears and discover how they might manifest in our stories.

In this essay, we’ll explore the ancient origins of horror, focusing on how things like mythology, folklore, morality plays, and religious witch-hunting manuals shaped our early understanding of the genre. We’ll examine concepts of death and undeath in the ancient world, the exact nature of monstrosity, and the societal fears that these narratives grappled with. Through this exploration, we’ll reveal the lasting impact these ancient tales have had on contemporary horror, and the feast of fears they continue to evoke…

“It’s An Endless Cycle of Maggots…”

As October rolls around, many of us horror obsessives embrace the seasonal chill signaling the approach of Halloween. Outside, the leaves turn vibrant hues of orange and red. Jack-o-Lanterns light up our front porches, and the days grow shorter, casting longer shadows. As the weather grows cold, we sip on Pumpkin Spiced Lattes from the comfort of the fireplace and watch black and white monster movies till the early hours of the morning. October is a time steeped in themes of death and decay, mirroring nature as it prepares itself for a wintery sleep.

But for myself, living down in the southern hemisphere, here, in Aotearoa, Halloween takes place in a seemingly parallel world. As the north prepares for darkness, we welcome in the light. October is the back-end of Spring for us, and early signs of Summer are now starting to show. Here, the days lengthen and temperatures rise. Flowers and trees bloom, filling the air with the perfumed aroma of pollen. While others look towards the chilling embrace of death, in New Zealand, we celebrate the joyous reawakening of life.

The vibrancy of nature’s triumphant return, when constrasted against images of ghosts and goblins, witches and vampires, mummies and werewolves, is strange. But it makes me wonder how different cultures around the world have interpreted the cycles of life and death, growth and decay.

The ancient Romans, for example, saw death not as an end, but rather a continuation of life. For the people of their time, death was both intimately known, and at the same time, a terrifying mystery. To them, the dead did not really die. Rather, they transitioned into a secret world that was contained within our own. This belief allowed them a way to deal with the often sudden, unforeseen and unexpected tragedies that plagued societies in classical antiquity. They feared death not only because a loved one suddenly gone, but also because just as suddenly, they might come back...

While fears of Revenants were rife across the ancient world, the ways in which Roman society dealt with them is particularly interesting when attempting to trace the evolution of horror. It’s well-known that later societies such as the ones that have formed our own, often desperately aspired to be like the Roman Empire of the past. As a result, their culture has played an incredibly important role in the formation of Western thought - literature included.

So what did the Romans think exactly in this particular context? Well, they saw the dead as being both impure and dangerous. They believed that a corpse could easily become a threat. They felt it was important to make sure that these potential threats were appeased. And they believed that if they weren’t properly put to rest, they might rise and set out looking for revenge.

To the Romans, the dead were the cause of epidemics, of madness and supernatural possession. Those that suffered such possessions were known to them as Larvaetus, or those “Possessed by a larva” - aka, the spirits of the dead. In order to avoid these insidious attacks, the Empire held yearly festivals to honor the dead - Parentalia and Lemuria - are two we know of today. In fact, the poet Ovid gives us an interesting tidbit in relation to these festivals, showing us how seriously they were taken:

“But once upon a time, waging long wars with martial arms, they did neglect the All Souls’ Days. The negligence was not unpunished; for tis said that from that ominous day Rome grew hot with the funeral fires that burned without the city. They say, though I can hardly think it, that the ancestral souls did issue from the tombs and make their moan in the hours of stilly night; and hideous ghosts, a shadowy throng, they say, did howl about the city streets and the wide fields. Afterwards the honours which had been omitted were again paid to the tombs, and so a limit was put to prodigies and funerals.”

Ovid. Fasti, Book 2

I don’t know about you, but that sounds like an ancient Zombie apocalypse to me!

To them, the dead were believed to have power because they continued to live on in their tombs. During funereal rites, the living would announce to the deceased “Take good care of yourself!” before adding, “May the earth be light upon you.” The deceased were then called by their name three times as a way to recognize their identity and stop them from returning. The soul was even outlined within Roman law, described as remaining within the body, until a series of complex rituals were conducted. The ignoring of such rites, would result in the dead becoming outraged or dissatisfied, allowing them to return and trouble the living.1

These dangerous entities were known as the evil dead (hmm, sound familiar?) and they were typically those who had experienced violent deaths. Murder, execution, drownings, suicide, or any that occurred before the “fated day” of death. Many were criminals, as criminals were often denied the right to a ritual burial. The Roman poet Horace writes that:

“Now you can live on a healthier Esquiline and stroll, On the sunny Rampart, where sadly you used to gaze, At a grim landscape covered with whitened bones. Personally it’s not the usual thieves and wild creatures, Who haunt the place that cause me worry and distress, As those who trouble human souls with their drugs, And incantations: I can’t escape them or prevent them, From collecting bones and noxious herbs as soon as, The wandering Moon has revealed her lovely face.”

Horace. Satire 1.8. Priapus on the Esquiline.

Revenants weren’t always confined to rotting bodies either. They could also come in the form of Ghosts and Specters. In ancient Greece, Pliny the Younger records an anecdote from Athens about one such entity, stating:

There was a haunted house in Athens that was rented by the Philosopher Athenodorus. He saw a specter wearing manacles on its feet (compedes) and wrists (catenae), and the specter beckoned him [Athenodorus] to follow him into the courtyard, where he disappeared. The philosopher got authorization to excavate this location. A chained skeleton was unearthed and given a public funeral ceremony. The apparitions then ceased.

Horace, Epistolae VII, 25, 5.

This story of ghostly revenants ties to an ancient and expansive belief across Africa, Europe and even into parts of Asia. The belief that the soul was housed within a creature’s bones. This was typically connected to hunter-gatherer traditions, and ritualistic attempts to re-wild hunting grounds with fresh game. Often the bones of larger animals would be gathered in piles, or baskets, while their skins were stuffed with wood shavings and straw. Through a spell, the god of sacrifice would restore them to life, making them even fatter than before.

In the Edda by Snorri Sturluson, we see an account of this tradition:

“[Thor is traveling with Loki in his card, which is being pulled by some goats.] At nightfall, they arried at a farmer’s house and obtained permission to spend the night there. That night, Thor took his goats and killed them both. Then they were skinned and placed in a cauldron… [Everyone is having a meal.] Thor put the goatskins between the fire and the door and told the farmer and his people to place the bones on the skins. But Thjalfi, the farmer’s son, kept one of the goat’s thigh bones and craked it with his knife to get to the marrow… [In the morning, Thor takes his hammer Mjölnir, brandishes it and recites] incantations on the goatskins. They were brought back to life, but one of them was limping, favoring his back foot.”

Sturluson, Snorri. Prose Edda. Book 2: Skáldskaparmál.

The concept of the soul of bones was not limited to animals. Anthropological evidence shows us that among Shamanistic peoples - such as the Turko-Tartars and the Siberians, the soul of a man was also said to reside in the bones.

The claim that this belief, or any other was wide-spread across large geographical locations prior to the rise of Christianity, is one that has been debated amongst scholars for sometime, but while we may not be able to claim a one-for-one comparision, there definitely appears to be a certain continuity of these sorts of archetypal ideas across history and multiple cultures. This concept of the Soul of Bones in fact, is so prevailent that it has managed to survive from ancient times relatively unchanged all the way to modern horror films. In our spooky classics, Houses plagued by evil spirits are often built atop disturbed burial grounds (Poltergeist, The Amityville Horror,) and the undead are regularly dispatched through methods like salting and burning their bones (the TV show Supernatural is one example of this.)

The pervasive beliefs around Revenants in antiquity, whether they have to do with anger towards the living, or what binds them in their undeath, is fascinating in that it reveals to us a widespread multicultural concern. One which continues to resonate today. That concern is this:

What actually happens when we die?

Societies like the Romans, the Greeks and the Norse (among many others) each grappled with this existential concern in remarkably similar ways. They feared untimely death. They sought to appease the victims of it. They took precautions to protect themselves from these they were unable to appease. And they told horrifying stories warning about what might happen if they didn’t remain vigilant.

Today, these fears have evolved, but remain embedded in our collective minds. Now, instead of rituals and traditions, we explore this fear through horror stories, searching just like they did, for an answer to life’s most concerning question.

“…Slithering Putrid Things…”

Of course, not all horror stories deal with Revenants or the different forms of the undead. Others deal with monsters. And just like our horror stories today, the mythologies of antiquity also explored all manner of scaley, fury, and fire-breathing creatures. We all know these kinds of tales: Medusa the Gorgon, the Minotaur in his Labyrinth, the Dragons of Japan and China, Giants, Griffins, Elves, Oversized wildlife and more. These are creatures designed to explain the unknown, or to illustrate caution, or act as foils to the heroes that face them. They’re dangerous for sure, but in most cases, not particularly scary.

So, what’s happening here? What is it that differentiates a beast of myth from one of horror? And why have some of the classics made that leap into the darkness, whilst others are take up residence in whimsical children’s fantasies regarding wizarding schools?

In his book The Philosophy of Horror: or, Paradoxes of the Heart, Noel Carrol provides what I feel is a fascinating and insightful categorization of the two:

“…What appears to demarcate the horror story from mere stories with monsters, such as myths, is the attitude of the characters in the story to the monsters they encounter. In works of horror, the humans regard the monsters they meet as abnormal, as disturbances of the natural order.”

Carrol, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror: or, Paradoxes of the Heart. P.14

Carrol explains that characters in a horror story react to monsters through fear, yes - but not only that. The threat of fear is “compounded with revulsion, nausea, and disgust.” Monsters in horror stories are often described as:

“…impure and unclean. They are putrid or mouldering things, or they hail from oozing places, or they are made of dead rotting flesh, or chemical waste, or are associated with vermin, disease, or crawling things. They are not only quite dangerous, but they also make one’s skin creep. Characters regard them not only with fear but with loathing, with a combination of terror and disgust.”

Carrol, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror: or, Paradoxes of the Heart. P.14

It seems to me, that the mythological creatures who successfully make the jump to horror, are those that have an inherent capacity to symbolize deeper and more disturbing ideas. Whilst figures like Medusa or the Minotaur begin as symbols of caution, warning listeners of the dangers of hubris or human desire, at some point they were able to transition. They became modular narrative building blocks that could easily convey themes like isolation, betrayal and depravity. They could do this because whether on purpose, or by accident, the lore surrounding them already already leant itself to a greater kind of darkness.

In one tradition, Medusa and her sisters are the offspring of gods, but in another, she is a high priestess of Athena. After being raped by the sea god Poseidon inside Athena’s temple, poor Medusa finds herself cursed by the goddess of wisdom and warfare herself. In a stunning display of victim blaming, Athena transforms Medusa into a hideous monster instead of absolutely destroying Poseidon. With this version of the story, we can clearly see these darker elements at play. Though the original evils here are perpetrated by divine beings, it’s pretty commonly understood that the gods of Olympus were more like humans than the deity we are used to hearing about in our current era. The story of Medusa stands as an early example of this idea that monsters aren’t born, they’re created instead.

In the story of the Minotaur, we see the same kinds of elements allowing for a seamless transition into horror. The Minotaur itself is a creature born through divine punishment, betrayal, and violence. He is an abomination that is somehow both pathetic and deadly. In the myth, he is the result of Queen Pasiphaë’s unnatural union with a bull - brought about by a curse from Poseidon (This guy again?!) after her husband refuses to sacrifice to him. The Minotaur is born, and almost immediately confined to a dark labyrinthine prison. Once fully grown, he embodies the shame and violation of natural order that brought him into existence.

Here, we see themes of monstrosity exploding all over the place. We have King Minos’ pride tied directly to his unwillingness to sacrifice, as well as his shame over his wife’s monstrous offspring. Then there’s Pasiphaë’s unnatural desire itself, put upon her by Poseidon’s wrath. And while beastiality was not as taboo back then as it is today, the union of a woman - a queen no less - with a beast-of-burden would have been a scandalizing idea, even back then.

The labyrinth, too, is key to the horror of this tale. It is both a physical maze and a symbol of confusion and fear. It’s a horrifying fate for any infant to be ripped from their mother’s arms and cast into a prison. An infant minotaur is no exception.

If we move away from the stories found in the Mediteranean, other myths, like those from further North, show us similar things. For example, let’s consider some of the stories focused around faeries and their terrifying intrusions on the human world. Whilst we can point a direct line to the fae as originating in places like Ireland, they actually tend to appear all over this geographical region. These strange ethereal creatures become horrific with ease, used as they were, to try explain the trauma experienced by the population in a time where medicine and scientific knowledge were lacking.

For example: Doppelgängers, or "fetches," were often seen as bad omens. They brought with them either death or bad luck. Sometimes they’d appear as doubles of a person, at others, they would manifest as a shadow, jealous of the life held by its physical counterpart. In many examples of lore dealing with these beings, the shadow was thought to straddle the line between the worlds of the living and of the dead.

“Quite gnerally known in all of Germany, Austria and Yugoslavia is a test made on Christmas Eve or New Year’s Eve: whoever casts no shadow on the wall of the room by lamplight, or whose shadow is headless, must die inside of a year. There is a similar belief among the Jews that whoever walks by moonlight in the seventh night of Whitsuntide, and whose shadow is headless, will die the same year. There is a sying in the German provinces that stepping upon one’s own shadow is a sign of death. Contrasting with the belief that whoever casts no shadow must die, is a German belief that whoever sees his shadow as a duple [Double or Doppelgänger] during the epiphany must die.”

Rank, Otto. The Double: A Psychoanalytic study. Translated by Harry Tucker, p.50

Such beings, symbolized the existential fear of losing one's own identity. They were explanations of the bizarre or troubling, such as mental illness or sudden personality changes.

Similarly, stories in which human children were being abducted by malevolent faeries and replaced with an imposter, or Changeling, likely originated as a way soothe the devestation parents felt after losing a child to famine, plague or other unknown illnesses. While having your kid abducted is still terrifying, it is perhaps easier to believe your baby might be alive out there living in a magical kingdom, than to accept the harsh and pointless realities of a cruel world.

What we see with Medusa, the Minotaur, Doppelgängers and Changelings are modular building blocks that can each be defined by common threads. Asides from naturally lending themselves to those deeper, more unsettling themes, all of them are connected in either a physical and/or mental way to us humans. Medusa and the Minotaur are beings with half-human forms. They are unholy chimeras, yes; but they also reflect the horrors of being trapped between two natures, unable to embrace either. While Doppelgängers and Changelings are their own “species,” they’re described as being humanoid, have human-like intellect and steal from humans in one way or other.

With all of these examples, there is also a certain “othering” of the creature. A singling out that adds layers of tragedy and revulsion to them. Though they may be a part of, or exist within human societies, they are not of us. Instead, they are feared and hated. They act as scapegoats for our own sins. When we think of them in this way, it becomes clear why those of us who grew up as gay, tend to identify with the monsters in horror films. One can only imagine those who were different back then may have felt a similar way.

When we consider the Revenants, the Ghosts, and now the monsters of mythology and folklore in the context of horror, we see that each acts as a kind of mirror, reflecting our own dark images back at us. They are more than just fictional demons. Instead, they are archetypal shapes that allow us, through story to grapple with things like morality, social fears and the all pervasive concern over what happens when we die.

“Burn Them All! Let The Witches Burn!”

The fears of the ancient societies we have just discussed, particularly those regarding the power of women, had a profound influence on the ways in which organized religion began to develop in the wake of the Roman Empire’s collapse. From the time of the early Christian Church, where Apostles commanded women to be silent, to the systematic persecution of “witches” centuries later, the shift from antiquity to the Middle Ages birthed new anxieties into our world.

Echoing earlier mythological representations of dangerous women, the monsters feared during this time came to include creatures defined by their femininity, or their sexual desires. Medieval tales of the Loathly Woman, or Catholic fears of Succubus and Incubus demons are a couple of great examples.

Whether the Church genuinely believed that these supernatural beings were real, or simply demonic imaginings depends on which camp one planted their theological flag, but what is clear, is that those in power saw certain people and their ways of life as opositional and a dangerous threat to their own grip on power. Female and sexual figures became tropes within the Christian framework, and were used to stoke genocidal fears, which of course, resulted in the early modern Witch Trials across the European continent.

These trials reached their height with the publication of a dispicable, but important text of the time. The Malleus Maleficarum or Hammer of Witches written by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger in 1487, provided a detailed manual on identifying those in-league with the devil, and how to prosecute them. The Malleus Maleficarum served not only as a legal guide, but as a template for other similar texts:

Discours Exécrable Des Sorciers by Henry Bouget (1602)

Tableau De L'inconstance Des Mauvais Anges Et Démons by Pierre de L’Ancre (1612) - which in addition to Witches, deals with hunting and persecuting Werewolves, and…

De Masticatione Mortuorum In Tumulis by Michael Ranft (1725) - which translates to The Chewing of the Dead in Their Tombs and explores how to combat Vampirism.

While Bouget and de L’Ancre applied the witchhunting methods of Malleus to witches and werewolves, Ranft’s work built on the Malleus’ preoccupation with spiritual corruption of the physical body, extending his focus to folk tales surrounding vampires and religious anxieties related to sexual sin. Additionally, later representations of vampires would evolve to embody anti-Semitic fears concerning Jewish immigrants.

Despite the supposed “non-fictive” nature of these kinds of religious manuals, when we look at them, we can see striking similarities between them and the soon-to-come boom of horror literature. These texts often featured vivid and exploitative descriptions of demonic possession, infernal or demonic magic, and grotesque punishments for those guilty of following Satan. By casting the accused as agents of the Devil, witch-hunting manuals were able to hijack the modular narrative building blocks established through mythology and folklore, and use them to demonize those they disagreed with, providing a justification for the atrocities they sought to visit upon them.

Of course, today, looking at all this from a wiser, more tolerant perspective, we know that these manuals were in fact, works of fiction. Setting aside the real-life evils they unleashed on minorities throughout this period, these manuals can actually be seen as proto-horror novels.

And as these witch-hunting manuals drove fears of supernatural evil into real-world persecutions, Morality Plays served as another significant medieval vehicle for moral instruction. These stories utilized allegory to depict the eternal struggle between light and darkness. They were plays featuring archetypal characters like the Everyman, Death, and Sin designed to illustrate moral lessons and the spiritual journey of the soul. Popular during the late Middle Ages, they focused on indoctrinating audiences on the consequence of sin, and the joys of redemption.

One of the most notable examples is the play Everyman, which follows the titular character on a journey to confront death, where he must account for his life and face judgement for his sins. the clear dichotomy between good and evil presented in this play mirrors the moral themes explored in modern horror stories. Morality often plays a significant role in horror, leveraging fear as an educational tool. In some cases, it can even serve as a contrast, allowing us to examine whether the morals presented are truly beneficial. Horror is often considered by some scholars as being a deeply conservative and reactionary genre, but in this sense, I would argue it at the very least, has the potential to be the polar opposite. Horror, when it challenges the established norms - particularly if it is in search for a new, better, answer - is perhaps the most progressive, and dare I say, the most aspirational genre out there. But that’s just my two cents.

However, in the context of the Middle Ages, horror was highly conservative, and rooted in very real spiritual stakes - eternal damnation versus eternal salvation - serving as a deterrent against sin and a potent mode of religious propaganda.

“And As The Crimson Curtain Starts To Fall…”

We can see now that horror has consistently engaged with the consequences of moral, societal and spiritual transgressions. Throughout ancient history and into the Middle Ages, it has been used as a way to explore the repercussions of human disobedience towards whatever beliefs were held dominant in a particular society at a certain time. This thematic lineage can be observed in contemporary examples like The Witch or Drag Me To Hell, where protagonists are judged for their sins and forced to confront them whilst enduring overwhelming terror.

Ultimately, the convergence of mythology, fears around death and the undead, and religious anxieties towards women and other marginalized groups, laid the groundwork for the emergence of the horror genre to come. Soon, we would begin to see early forms of a consistent literary genre. Next, would come the Gothic Romance, and after that; Gaslight Horror and the famed Penny Dreadfuls…

And as we reach the end of the long dark tunnel, only to discover a black tower, now looming before us, we can, now hopefully see, that the portrayal of human perversion, the othering of outsiders, and the stoking of religious fervor, not only shaped the horror narratives of their day, but also that of the ones to come. Now, as we step through the tower doorway, and take our first steps up the rickety, gloom smothered spiral, we can push forward with the understanding that by knowing and understanding the fears of her collective past, perhaps we can learn a little more about the ones we have today - and; perhaps those we are yet to have, in the future.

Happy Halloween,

Nick

Lecouteux, Claude. The Return Of The Dead. P.53