In the terrifying 2016 indie horror film A Dark Song, a troubled woman named Sophia rents an isolated house in rural Wales before hiring a foul-tempered ceremonial magician named Joseph to help her perform a six-month-long angel summoning ritual found in The Book of Abramelin (a real-world grimoire, by the way). If successful, their endeavours will summon Sophia’s guardian angel and allow her to ask of it one favour. Planning to use this favour to see her murdered son again, Sophia locks herself in the house with Joseph and the two begin a nightmarish journey into darkness. One of the initial actions taken by Joseph to prepare for the ritual, is to pour a line of what looks like salt around the border of the house. In his words, this:

“…is your last chance to back out. Once I complete the circle, no-one can leave until the invocation is done. Not for food, not for emergency, not for anything.”

In fact, circles appear frequently throughout A Dark Song:

“The circle is a paradox. No beginning and no end but bounded. In each circle there are four essential phases. We consecrate the circles, open the chamber…”

“Five circles, five elements, five realms.”

“This circle, this is the Chamber of Effect. Element of Wood, where we seal our vessel from the world, make it safe against attack.”

“Now this middle circle, this is nameless. This is where your angel will appear. You will ask your favor and I will ask mine.”

“No talking. For the next two days. I’m gonna unshackle the house from the world. You mustn’t leave the circle. No food, no water…”46

Later, when Sophia becomes frustrated that the ritual isn’t moving fast enough, she attempts to leave the house:

SOPHIA

I’m fucking going.

JOSEPH

No, no no! Don’t open the door! Don’t cross the line (the salt circle surrounding the house), we’ll be fucked. Cross the line, we’ll be stuck here forever. Please, you don’t – you just don’t know.1

Sophia reluctantly returns to the house, having seen Joseph’s terrified reaction. The two continue the ritual, and it isn’t long before stuff starts happening. As Joseph explains, they’ve “been noticed.” The rest of the film plays out like all good horror films – the characters fall victim to the scares of demons and spirits from the other side as they attempt to reach the conclusion of their quest. Eventually, out of terror, Sophia does leave the house and passes over the circle, foregoing her only form of protection. She finds herself in a ghostly version of the world, a kind of limbo. Purgatory. No matter how far away from the house she runs, she always ends up back where she started. As night falls, she realizes she’s trapped, and with the demonic spirits now able to hurt her, she has no choice but to complete the spell and summon her angel if she hopes to survive.

MAGIC CIRCLES

What we are seeing in A Dark Song is a reoccurring motif in occult and folk-literature. The motif of the Magic Circle. The Magic circle has been suggested to originate with the Zisurrû, an ancient Mesopotamian ritual in which a circle was drawn using a flour-based paste around a ritual space as a means of purifying the area or protecting it from evil influence. It was used in various situations – drawn around special figurines to thwart dark spirits, around the bed of a sick person to protect against ghosts and demons, or as a component of a larger ritual.2

The concept of a Magic circle has survived with us all the way from Mesopotamia (c. 3100 BCE – 539 BCE) and has found its place today modern occult religions like Wicca, as well as in entertainment as the above example shows.

In his book, In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy vol. 1, Eugene Thacker explores the use of the magic circle and its purpose in both occult systems and popular culture:

“…the magic circle maintains a basic function, which is to govern the boundary between the natural and the supernatural, be it in terms of acting as a protective barrier, or in terms of evoking the supernatural from the safety inside the circle.”3

In fact, Magic circles have been long incorporated into the lexicon of games and virtual worlds. In a 1938 book by Dutch Historian Johan Huizinga, magic circles are explored:

“All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the ‘consecrated spot’ cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice etc, are all in form and function play-grounds, i.e. forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart.”4

For now, as we move forward with the chapter, keep in mind the following:

Magic circles consecrate a space.

Magic circles govern the boundary between the natural and the supernatural.

Magic circles create temporary worlds within the ordinary word.

Magic circles can summon spirits or protect the practitioner against them.

PENTACLES

Often found within a magic circle are occult symbols. Whether to summon a supernatural entity or for some other purpose, magic symbols are prevalent in both the occult application of circles and their depiction in entertainment media. One of the most famous symbols we see housed within a magic circle is of course, the pentacle or the five-pointed star. Pentacles also have a rich tradition dating back hundreds of years. The first documented appearance of the pentacle can be found in the 1500s, primarily in the grimoires Heptaméron – a short story collection by Marguerite de Navarre, and the more famous Key of Solomon, a Grimoire written during the Italian Renaissance, but as was the practice of the time, claims to have a much more ancient lineage – presenting itself as being authored by King Solomon of the Bible himself. The Key of Solomon contains within it, dozens of different pentacles – pentacles that aren’t always five pointed stars, but a wide variety of designs, each with different purposes for different spells. However, since pentacles are easily recognizable, we’ll be dealing with them as a motif going forward.

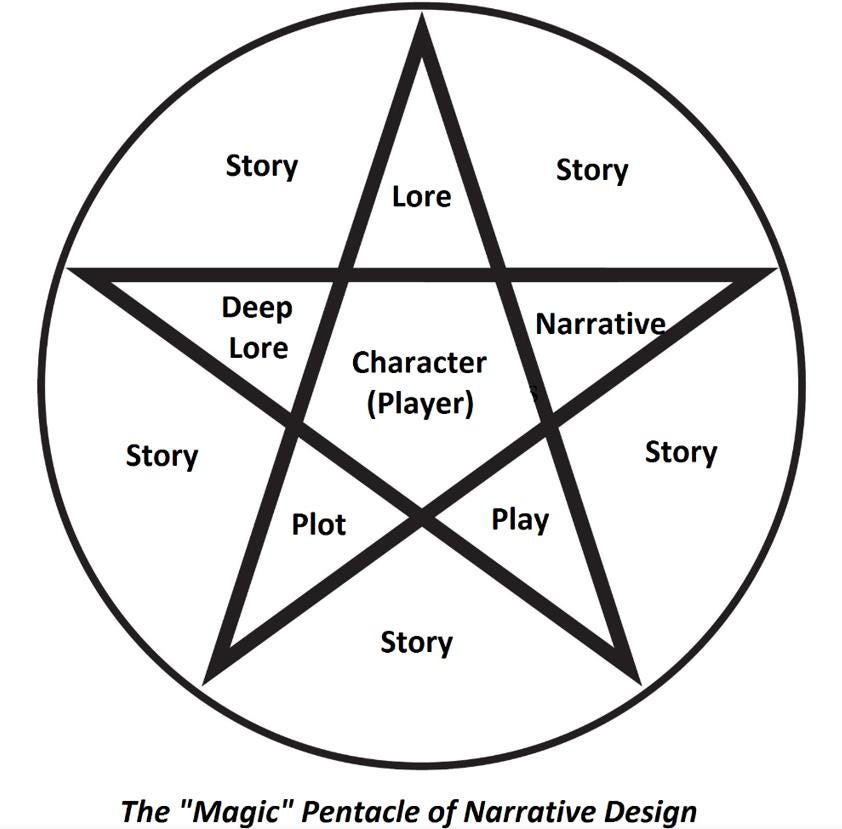

THE PENTACLE OF NARRATIVE DESIGN

The Pentacle of Narrative Design is something I’ve often described as a narrative structure, but in actuality, this is a bit of a misnomer thanks to the non-linear nature of interactive storytelling. In literary theory, a narrative structure describes the framework that underlies the progression of the plot.

The typical narrative structure you’ll see taught in creative writing classes around the world can be seen below. Beginning with introducing the setting and characters, the reader/audience are then introduced to a problem, which creates drama and rising action until we reach the climax, where things are as worse as they can possibly be. The protagonists overcome this final conflict and the action quickly falls as things return roughly to the normal world, where at last, we have a Denouement, in which things are resolved and we leave the characters to return to the real-world.

While this narrative structure technically works when we are considering the plot of a linear game, it does little to explain the ways in which a piece of non-linear storytelling is structured. Whereas traditional mediums like literature, film and TV move from one end of the line to the other, a line is inadequate to describe how the kinds of narratives we are exploring. Game narratives tend to… blossom outwards in all directions. Thus, let me introduce to you the Pentacle of Narrative Design (below) as an alternative way to understand the various parts at play in non-linear, interactive storytelling:

STORY: THE SACRED SPACE WITHIN THE CIRCLE

Remember back to a few minutes ago when I asked you to keep in mind three important facts pertaining to the magic circle? Yes? Let’s revisit them now:

The Magic circle consecrates a space.

The Magic circle governs the boundary between the natural and the supernatural.

The Magic circle creates temporary worlds within the ordinary word.

The Magic circle can summon spirits or protect the practitioner against them.

In this context, the magic circle does all these things for the player. It consecrates (sets apart) a space for the player to engage with something beyond themselves. It governs the boundary between the natural and the supernatural – by which I mean it allows a space for the fantastical to supersede the normal (immersion). It creates a temporary world within our ordinary world. And it summons spirits (NPCs, Enemies, etc) for us to engage with.

Story is what the magic circle summons. Story, and in this context, the game world itself. Everything that has been created to express the intentions of the developers to the players – the art that lets us feel something greater than our little lives on this little planet, in this vast universe. When we talk about story, we’re talking about the game in its entirety – characters and events, yes, but also gameplay, SFX, VFX, level design, and so on, and so forth. Story is what the player picks up and buys in the video game store or online. Story is a consecrated and sacred space to the player, which means two things:

We as designers have a responsibility to guide them into an emotional, transcendent experience. Anything that breaks immersion or creates ludonarrative dissonance for the player is something we need to try to remove from the work.

Anything that gets in the way of that experience – in game purchases, loot boxes, whale-hunting and other such corrupt monetization’s which prey on the neuro-diverse or those with gambling addictions, have no place in the magic circle. These are unethical practices which detract from a truly powerful experience and will only hurt your game, your fans, and yourself in the long run. The real way to create an evergreen game is to deliver a product that emotionally resonates with players. Get that right, and then maybe you can charge extra for a couple of DLCs.

LORE: THE HEAD OF THE PENTACLE

The Digital Jam VR Writers Room White Paper (now very hard to find online – message me if you want a copy!) spends significant time detailing the creation of immersive virtual worlds. While the paper is geared primarily towards Virtual Reality, much of the content around world-building and narrative design crosses over easily into any interactive medium. Specifically, the white paper considers the question of how one goes about creating a story bible and story world for players to explore and get lost in.

“Attention to detail is a fundamental of good story world-building. Crafting richness and nuance to even the smallest, less focal elements can create multiple layers of depth that enhance the sense of immersion. Whilst we may not need to see behind the present setting, knowing, or having a sense that something interesting and substantial what lies beyond it [sic] creates a sense of depth and completion for the world that the audience is being invited into.”5

Lore is a focused approach to crafting the richness and nuance described by the writers of the VR Writers Room white paper and is made up of all the generalized world-building of a game. It’s everything from geography, language, culture, and religion, to biology, horticulture, history and much more. Everything your game needs to exist as a believable world where actual people (or creatures) can reside.

Many have asked me over the years, how much lore is enough lore? Well, I’m a firm believer that the more, the merrier. Some might warn about focusing too much on world-building, becoming fatigued or losing sight of content that players are actually going to definitely see, but I’ve found that as long as you are disciplined in your creating, pages upon pages of world building is only going to help, not harm you. Do not be afraid of writing content players may never see. In-house lore content still has an important place within a story bible or game development document, as it allows others in the development pipeline to immerse themselves in the world and be influenced by it in the creation of their additions to the game. Extra content can also always be used in extensions of the base game (DLCS, Sequels etc.) or in transmedia offshoots (comic books, web series, movies, tv, etc.)

DEEP LORE: THE LEFT HAND OF THE PENTACLE

Depending on how you look at it, Deep Lore is technically a sub-section of lore, but for our purposes, we’ll explore it as a separate point in the pentacle star. Deep lore is named because of the depth it brings to a player’s understanding of the world and events of the story. I define it as all the world-building elements in your game that are crucial to understanding the plot and ultimately, the message of your game. Deep lore describes a specific style of world-building. One that focuses on crucial elements like character backstories, the cosmological rules of your game, structural politics etc. Deep lore consists of information that does not fit into the immediate plot but brings to light why things are the way they are or foreshadows how they will end up.

Elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo – A star shines on the hour of our meeting.6

Above is a Quenya (Elvish) greeting uttered by Frodo the first time he meets Gildor Inglorion, an Elf of the House of Finrod. The Elvish language brings a sense of realism to the cultural world-building of Middle-Earth and as such would be placed in the Pentacle under the first point in the star – Lore. Knowing the language of Quenya is not crucial to the reader for them to understand the plot. But, when we consider the character of Smeagol and how he became Golem - context for his mad quest to recapture the one ring, we see something different. This backstory is information we need to know if we are to understand Golem’s motivation in the immediate plot. Specifically, it effects how he relates to both Frodo and Sam as he guides them to the slopes of Mount Doom.

If The Lord of the Rings trilogy took place in the form of an interactive narrative (and of course it has, to varying degrees of success), then this information, having happened prior to the Protagonist starting their journey, would not be immediately known. The Player would have to actively seek out that information in order to understand Golem’s eventual betrayal and his tragic end. This is an example of Deep Lore.

“But Nick!” you might ask, “Isn’t that just exposition?”

Well, yes. It is. But in a game, it is special kind of exposition. Exposition that the player will need to seek out themselves. This means as a Narrative Designer, your job is to find a way that ensures the player comes across it. Without throwing it in their faces of course.

Subtlety is key.

NARRATIVE: THE RIGHT HAND OF THE PENTACLE

Narrative concerns itself solely with the mode of telling that is being used to convey lore, deep lore and plot to the player. Narrative is similar to Story in the sense that it is a meta-fictive element at play in the development of a game. Like Story, when we talk about Narrative, we are talking about the game as a whole. Story is high level design. Narrative is still high level, but it’s slightly closer to the ground. When we discuss narrative, we are discussing the tools that we want to use to present information to the player. Narrative relates directly to the working parts of the game’s story – NPCs, Items, Enemies, Text-based pick-ups, audio-based pick-ups, music, visual style and tone, level design, etc. How do these disparate elements all come together to tell the story of our world? How do they guide the player through deeper themes and/or philosophical questions being posited by the developers, so that they might be immersed and meet with eventual transcendence? Story might be a painting of a house, but Narrative is concerned with the different paints and brushes that the artist used.

Consider the 2020 Samurai masterpiece by Sucker Punch Productions, Ghost of Tsushima, which displays an unusually beautiful use of narrative to deliver story information to the player. A common task required of the player in open world roleplaying games is to navigate a large open world. This task drives the player from one story event to another. Often, the mechanics in place that allow this task to be fulfilled are a little clunky and quickly descend into the following: In the corner of the screen, you might find a little GPS map, and as you play, the game forces you to focus on that, and the little X or bleep or star or whatever, to know where you’re going. You follow a dotted line across the world to get from A to B.

As great of a game as it is, The Witcher III: Wild Hunt is, I find, highly guilty of this approach to navigation. A staggering 81 million dollars US was spent on developing this game over three and a half years – and all I’m doing is watching that little map sitting in the bottom corner of the screen!7 I could be immersing myself in this stunning world, but instead, I’m trying to figure out where the hell I am.

Ghost of Tsushima on the other hand, attempts to find an elegant solution to this problem by considering navigation as a form of narrative delivery system. By using the folklore of Japan as a jumping off point, it creates a player experience that captures the peaceful introspection and exhilarating violence of a Samurai power fantasy. Swipe on the PS4 touch pad or select a spot on the in-menu map, and a guiding wind blows in the direction of your goal or destination. This guiding wind is grounded within Shintoism and does away completely with the GPS map approach, allowing you to instead, enjoy the world around you.

In the indigenous Japanese belief system, god-like spirits named kami are found throughout nature – in trees, rivers, animals, and yes – even the wind. Further strengthening this connection, Ghost of Tsushima provides other unique forms of navigation for the player to discover: As you pass through an ancient forest, you might spot a friendly red fox, or golden bird flittering through the trees. Either creature, if followed will attempt to lead you to a secret hidden just off the beaten path. Foxes in Japanese tradition are spiritual animals, and so guide you to hidden shrines, where praying at them will grant you special charms. The golden bird, seen as a good omen in Japanese myth, also leads you to various secrets and treasures. Taking this idea even further, the game could had provided a meditation mechanic (rather than using an in-menu map), where the player has their character think on certain concepts corresponding to different shrines, collectables or quests. Those thoughts could then trigger the guiding wind to lead them to their destination. The game could have even introduced a nefarious guiding wind, that could trick players, drawing them into traps, just like folk superstitions from around the world suggests of the will-o’-the-whisp - ghostly lights that try pull travellers off the road and into dangerous forests or swamps.

PLOT: THE LEFT FOOT OF THE PENTACLE

Deep Lore might be a difficult concept to enact in the creation of a game. On the flip side, plot is relatively easy. Plot in interactive storytelling is much the same as plot in other story-based mediums – with a few amendments. Plot is everything that happens to the player (or around the player) in real-time as they engage with the game’s systems. It’s what happens between that opening cinematic, and those final credits. It’s the player (and protagonist) moving from point A to point B or, I should say, point A to point B, C, D or E.

Game plots are non-linear. They need to give the player a sense that they’re working towards something, while at the same time being fluid enough that certain plot points can be encountered in whichever order the player encounters them in. Do this right, and you have an elaborate immersive experience. Do this wrong, and the player can’t help but feel that the game is breaking down, collapsing slowly around them. Plot can make use of whichever narrative model you like, however – and we’ll draw from screenwriting theory here – depending on the genre of the game you’re building (narrative genre rather than gameplay genre), your plot will be built of two parallel branches from start to finish. These parallel branches are called through-lines. One is your action through-line and the other is your relational through-line. Your action through line is exactly how it sounds.

This is what we would normally consider as the player journey in a game development doc: The player goes here, the player does this, the player fights that, the player becomes stronger, the player meets this faction, and so on and so forth. A relational through-line is the emotional journey undertaken by the player and protagonist. It plots the emotional beats between the protagonist and the NPCs of the world – particularly the NPC most important to that character (i.e. a love interest or family member). Often there’s an overlap between the action through-line and the relational through-line, but they should always be considered in the development stage separately so that each line stands strong on its own. Some genres do not require a particularly advanced relational through-line, and some won’t require one at all (a relational through-line in DOOM Eternal for example would detract from both the gameplay and story). That being said, both should always be considered, at least in the early stages of development.

PLAY: THE RIGHT FOOT OF THE PENTACLE

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we come to the concept of play. Play is all about the actions the players take to interact with the world and influence the progress of the plot. This is where a core gameplay loop (or loops) comes into the mix. In our magic circle, Play puts a specific focus on allying itself with the other elements discussed above. In this approach, the Narrative Designer is required to work as what I like to call a T person. A T person is an expert in one thing (i.e. the ascender of the T), while also knowing a little bit about a lot (i.e, the arm of the T). The Narrative Designer should be an expert in all things story, while having a bit of knowledge about all the other creative disciplines in game design. I’m not talking about being able to write and code (I myself have abysmal skills when it comes to coding), being a T person simply means that you have developed the ability to come alongside other developers in a game’s pipeline and work with them, championing all things story. It’s your job to guide and help make certain that the gameplay elements work in cooperation with the narrative to deliver an impactful story.

This is the bloody and beating heart of narrative design.

From Software really are masters when it comes to this kind of narrative design. We’ll touch on Dark Souls a little bit in the next chapter when we discuss how character can be utilized to create a new kind of immersion, but right now, let’s stop and consider two other games the studio has developed which display this union between play and story themes – Bloodborne (2015) and Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (2019).

Bloodborne is a Lovecraftian-styled horror dressed up in the form of a gothic action-adventure RPG. Thematically, the game is all about evolution (or de-evolution), desperation and hope in the face of an uncaring cosmos. As a hunter you progress through the crumbling Victorian city of Yharnam, killing lycanthropic beasts and facing off against tentacled Great Ones as you attempt to put an end to a supernatural blood disease that has ravaged the populace.

Bloodborne is an exemplary piece of strong narrative design for many reasons, but the one we are going to discuss right now, is how they imbue their combat loop with thematic potency. Like most games, Bloodborne gives the player what appears to be a health bar at the top of their screen. When you take a hit, the damage is represented briefly as a faded chunk of your life. If, upon seeing this, you leap desperately into the fray and strike back at the enemy, then that chunk will return to full colour and your health is restored. Wait too long, and it’s gone for good.

You see, in Bloodborne, we’re not really looking at a health bar at all.

Instead, your character’s life is defined by your will to live. This is a hope bar. How will you respond to a world of cosmic entities and demonic creatures that you are woefully unequipped to deal with? Will you steel your resolve and fight, or succumb to the darkness? By implementing this question into the mechanics of combat, the game aligns its ludological components with its philosophical themes, creating a unified story, as well as encouraging a fast-paced, frenzied and desperate fighting style in the player.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, also uses narrative design to marry its combat system to its core themes. As the Creative Director of all these games, Hidetaka Miyazaki states, the combat of Sekiro comes:

“…from the clash of steel between katanas. This constant clang, clang, between yourself and your foe that creates this intensity in the constant fear of death.”8

In the game, players are once again, given a health bar to protect, only this time, they are given a second bar as well. One that is arguably much more important: this is your posture gauge. Posture exists in the game as your character’s defence. When your posture is low and you are on guard, it is next to impossible for most enemies to cause damage to your health. However, every hit you take while guarding, will fill the posture gauge up. When the gauge can’t be filled any further, your posture breaks, and you open your character up for a death blow at the hands of your enemy. Likewise, your aim in battle is to break the posture of your enemy in the exact same way, allowing you to enact a death blow on them instead. A death blow removes either a significant portion of health, or kills you (or your enemy) entirely, depending on the difficulty level you are currently facing. You can hack away at your enemies, acting desperate and hostile (as is encouraged in Bloodborne), eventually filling up their posture gauge, but this will take a long time, and is risky as attacking opens you up to their blade as well. Instead, you need to break your enemy’s posture by deflecting their attacks. Deflecting requires hitting the guard button at the exact right moment, turning the combat of Sekiro into a kind of rhythm mini-game, where you hit your guard button in tune to the beats of an enemy’s strike.

Why is this combat gameplay so important?

Like in Bloodborne, this narrativization of a core gameplay loop serves to explore thematic elements of the game – in this case, it reinforces the values that the Protagonist, a Shinobi named Wolf holds in high esteem - discipline, technique, strategy and decisiveness. Whenever the player crosses blades with a challenger, these ideas are reiterated over and over all the way up until that final boss is felled.

ACTIVATING THE MACHINE

The end goal of the magic circle is thus: The player boots up a game and, in that act, crosses the salt line dividing the normal world from the special one. There, they inhabit the central point of the pentacle, which is character. Through that lens, the player is now free to explore the sacred space in whatever direction they like. They are informed gradually through various narrative techniques, about the story-world, becoming more and more immersed, until finally, immersion ticks over into transcendence – the moment in which they lose themselves entirely to the story you have created.

Footnotes

A Dark Song. Directed by Liam Gavin. 2016. Galway, Ireland: IFC Midnight, Film.

Lambert, Wilfred G. Wisdom, Gods and Literature: Studies in Assyriology in Honour of W.G. Lambert. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2000.

Thacker, Eugene. In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy. John Hunt Publishing, 2011.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1971.

Laird, Tanya, Rhianna Pratchet, Jeff Gomez, Charlie McDermott, Kathleen Wallace, Andi Ewington, Dave Cook, et al. Digital Jam VR Writers Room White Paper. Digital Jam Limited, n.d. Accessed , 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20180912143719/http://www.digitaljamlimited.com/.

Tolkien, John R. The Fellowship of the Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings. New York City: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2012. Reissue Edition.

Chalk, Andy. "The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt Cost $81 Million to Make." Pcgamer. Last modified September 9, 2015. https://www.pcgamer.com/the-witcher-3-wild-hunt-cost-81-million-to-make/.

"Hidetaka Miyazaki On Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice." Game Informer. Last modified August 21, 2018. https://www.gameinformer.com/interview/2018/08/21/hidetaka-miyazaki-on-sekiro-shadows-die-twice.