“Plagued by Ghosts…”

Last week, in celebration of the spooky season, I released the first part of this four-part series tracking the historical development of horror. In that essay, which you can read HERE, we looked at the genre’s origins in the context of classical antiquity. Drawing from various mythological and folk traditions we suggested that the multicultural fear of death, use of monsters to explain the unexplainable, and religious propaganda tied to the European Witch hunts, all formed the basis for the genre that we know today.

In this follow-up essay, we’ll leap forward a few centuries to discuss the emergence of horror as a distinct literary style. Beginning with the Gothic, we’ll touch on the concept of the sublime, before moving onto Gaslight Horror and its infamous Penny Dreadfuls. However, before all that, we do need to revisit the Medieval period one final time…

Horror is an expansive subject. We’ve seen this already. A complete examination would likely fill multiple volumes. For example, we could look at the beliefs of Agrarian cults, the influence of pagan holidays or even the works of a certain William Shakespear in relation to the genre’s formation, but to do so would quickly exceede the scope of this series. While all those factors do contribute, for this series, I’m only interested in what I consider to be the core vertibrae within horror’s spine.

That being said, there is one foundational text that I missed. One that warrants discussion as it is pivotal in influencing the works we are discussing today.

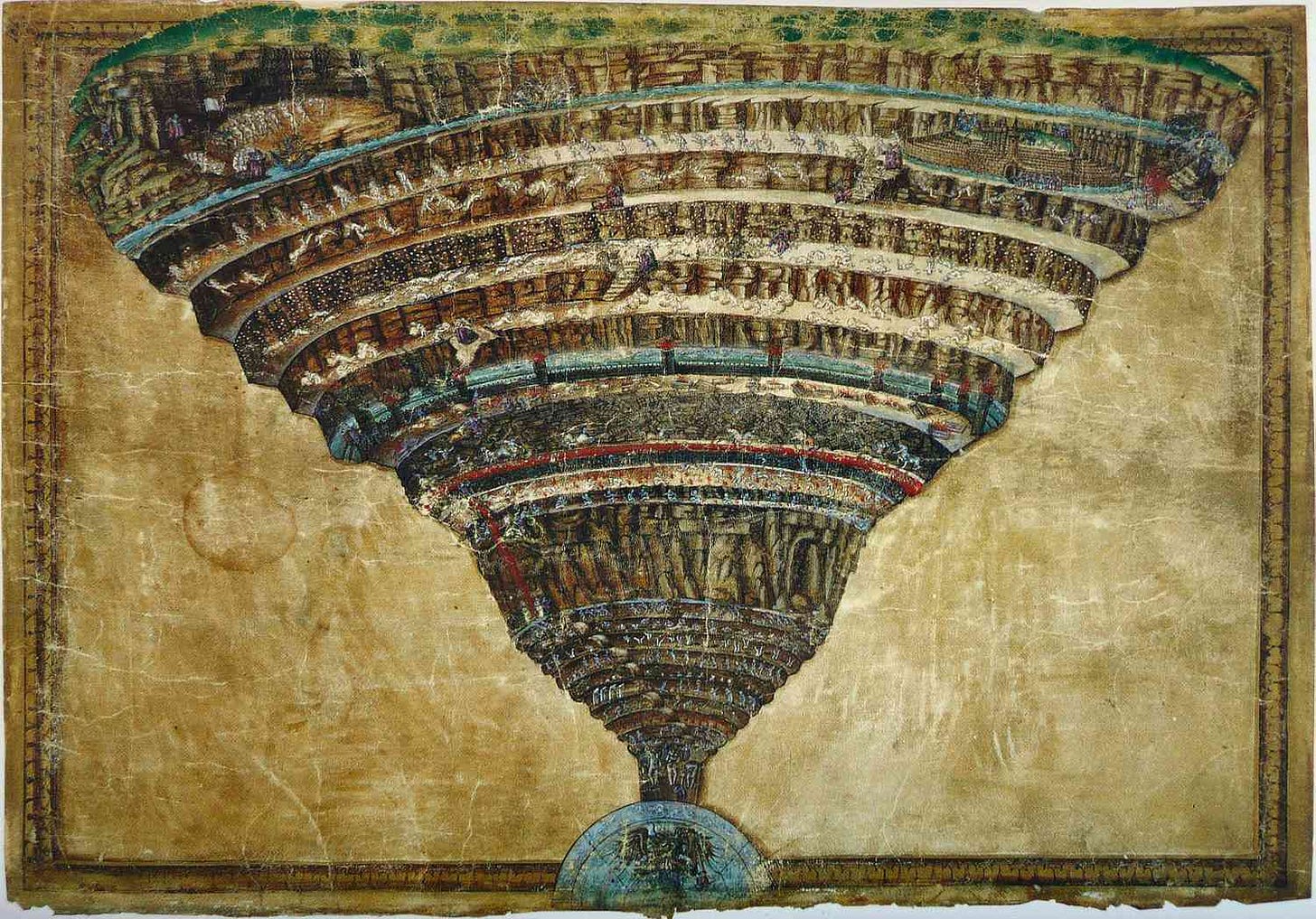

I’m talking, of course, about everyone’s favorite depiction of Hell—the epic 13th-century poem, Dante’s Inferno.

I’m sure we all have at least a cursory understanding of this text, but for those who have been living under a rock for the past seven hundred years, Dante’s Inferno is an epic narrative poem that follows the author (Dante) as he receives a guided tour of Hell, led by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. As Dante descends, he moves through the nine circles of the christian underworld, witnessing the various torments of sinners, until at last, he reaches the center where the Devil himself is imprisoned for eternity in the frozen lake of Cocytus. Whenever the Devil flaps his wings to try escape, icy winds create further torment for him. In addition, he is required to chew constantly on the three greatest traitors in history: Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius.

The reason why Dante’s Inferno is so important is that it functions as a bridge beween the fears of antiquity, those of the Medieval Church, and of Gothic horror.

In Inferno, we see the longstanding fears of the ancient world - death, the wrath of the gods, supernatural punishment, and terror of the unknown - reimagined through the lens of Christian cosmology. This reimagining would go on to heavily influence beliefs about the devil and demons during the European witch trials as well. Dante, as a writer, is a master at painting a powerfully vibrant depiction of Hell. In his narrative, the damned face punishments tailored to their sins—a concept that is still explored in horror stories today.

What’s more, Dante makes use of the unknown and its ancient associations with chthonic deities, evil spirits, and other worlds to reshape his Hell into a literarily impactful and complex setting. Much like the practices and beliefs of ancient mystery religions, where spiritual revelation - or gnosis - was often hidden behind intricate symbols, narrative structures, and dense philosophical concepts, the nine circles of Hell function on their own internal logic, rather than just relying on theological tradition.

Dante’s logic when compared to previous incarnations of horror stories is unique in that it introduces elements of psychological horror. Punishments aren’t just physical torture; they are also ones of the mind. In addition, those that are physical, the poet describes in almost exploitative and unsettling ways designed to provoke a physical reaction from readers. Dante’s aim is not just to provide a cautionary moral tale, but to induce revulsion, shock, and scandal at sin - an agenda that often features in horror to this very day.

Lastly, Inferno depicts a deeply personal journey for its protagonist. The Dante of the poem is not merely an archetypal heroic figure descending into the underworld, as in the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice; rather, he is an ordinary figure - an everyman - who embodies the often conflicted internal moral lives of real people.

Through these features, we see how the ideas of mythology are transformed into something relevant to Dante’s audience. We also see early genre signifiers developing that would later be used extensively in Gothic horror. The depiction of the Devil, for example, acts as a foreshadowing of the monster as a tragic figure rather than simply an embodiment of evil. This nuanced portrayal of the enemy of God could be seen as an influence on the Byronic characters of proto-Gothic works like Milton’s Paradise Lost, as well as the more refined Gothic horrors to follow, such as Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto and Stoker’s Dracula.

In fact, we could argue that it was Dante’s Inferno - more so than other examples of medieval religious horror - that influenced Gothic literature the most. In the period we are about to discuss, stories become less about sins and transgressions as being horrors in and of themselves, and more about how they can haunt the mind and warp the soul. Unlike other religious inspired texts of the time, Inferno reveals sinners as pitiful in addition to being heretics.

“Poetry… In The Tombs!”

The development of Gothic Horror arguably begins with a peculiar literary movement referred to today as the graveyard poets. But before we get to them, we need to understand the cultural climate that birthed their artistic vision.

The protestant reformation, beginning in the early 16th Century, prompted a shift away from traditional Catholic doctrines and towards individual interpretations on spirituality and the afterlife. Next, the Enlightenment period, in which scientific inquiry and rational thinking challenged superstition, contributed to a sense of freedom in re-examining old beliefs.

However, as the century marched onwards, certain groups began to resist these new paradigms. The Romantic movement, pivotal in this backlash, argued for the importance of emotion, spirituality, imagination and the sublime (more on that later!)

Around the same time, perhaps influenced by the traditions of the Momento Mori, along with an increase in medical knowledge, people began to consider death in more reflective ways. Artists and writers often explored death not just as some scary monster, but an inevitable part of life. The world’s socio-political climate during this period was also one of upheaval, war and political instability. Though people were more inclined to meditate on the nature of death, there was a collective sense of uncertainty about the future. As a result, darker themes of loss, and existentialism became particularly resonant.

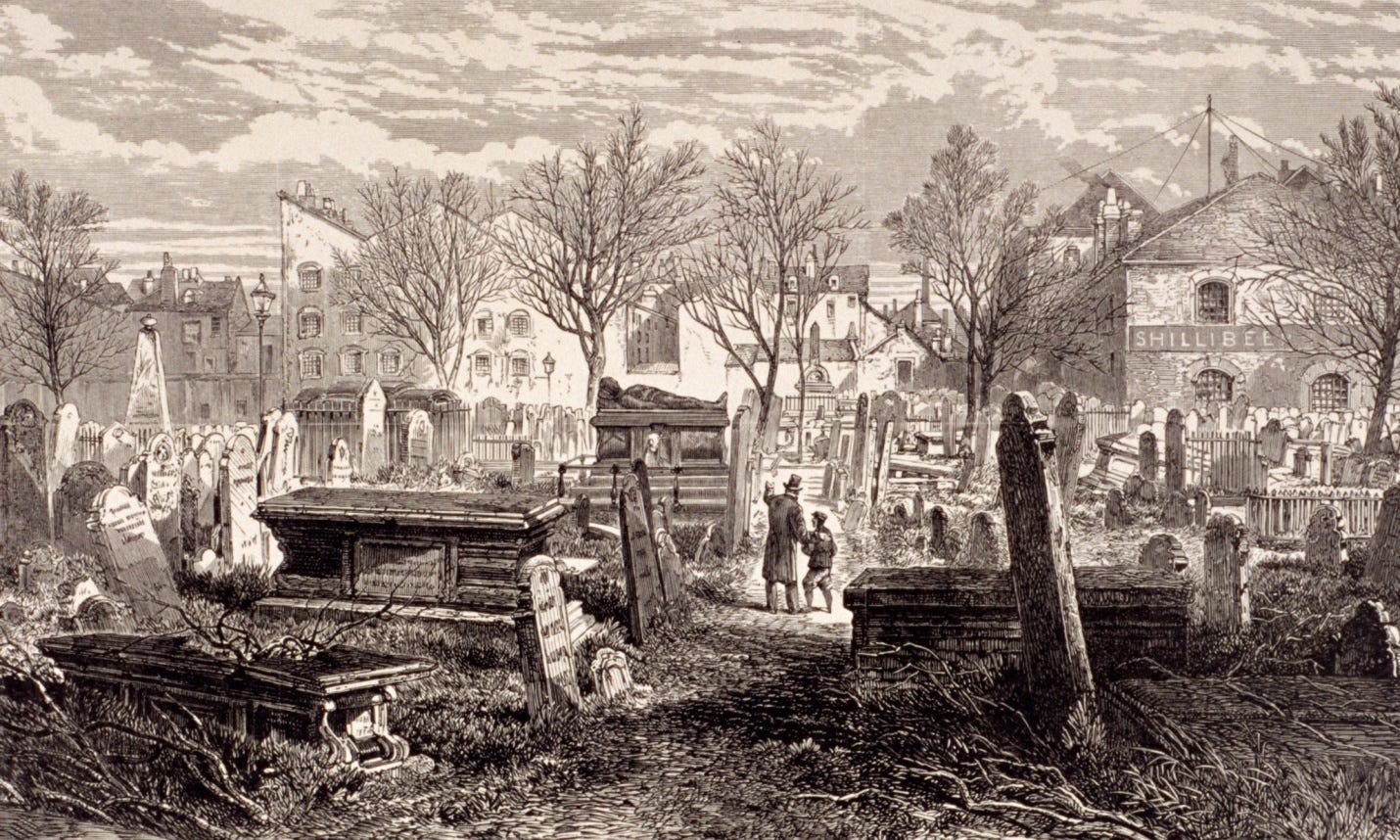

Finally, the 18th century saw changes in the way we dealt with our dead. Cemeteries were designed as places of peace, where the living could visit and sit with their lost loved ones. Tombs, crypts and monuments were constructed in ways that explored mortality through an artistic and aesthetic lens.

Enter into all this: The Graveyard Poets.

Beginning in 1714 with Thomas Parnell, and his poem A Night-Piece on Death:

“…Ha! while I gaze, pale Cynthia fades, The bursting earth unveils the shades! All slow and wan, and wrapped with shrouds, They rise in visionary crowds, And all with sober accent cry, "Think, mortal, what it is to die." Now from yon black and fun'ral yew, That bathes the charnel-house with dew, Methinks I hear a voice begin (Ye ravens, cease your croaking din, Ye tolling clocks, no time resound O'er the long lake and midnight ground); It sends a peal of hollow groans, Thus speaking from among the bones. "When men my scythe and darts supply, How great a King of Fears am I! They view me like the last of things: They make, and then they dread, my stings. Fools! if you less provoked your fears, No more my spectre-form appears. Death's but a path that must be trod, If man would ever pass to God; A port of calms, a state of ease From the rough rage of swelling seas…"

("night-piece on death," 2011)

Through his imagery of graveyards at night, Parnell examined death from a contemplative perspective. The “pale Cynthia” mentioned in the above excerpt, a reference to the moon, acts like Virgil in Dante’s Inferno as a guide through these meditations on death. Parnell’s message was that death was not something to fear, but rather, a doorway through which the soul reaches God. Parnell leaned heavily on themes from the Romantic movement, to do this, balancing his poem in the space between science and emotion.

Other poets such as Oliver Goldsmith, William Cowper, James MacPherson, Robert Blair, and Thomas Chatterton also contributed to this fascination with death and the afterlife, and together, they began the groundwork for the Gothic novel. The Graveyard Poets echoed ancient fears of mortality, the afterlife, and the dead, but reinterpreted them as something entirely new.

“The Chewing of the Dead”

As the Graveyard Poets continued to explore horror as a philisophical exercise, a growing revival in public interest about the supernatural flooded Europe. While there are many factors for this, the key moment in my opinion, comes to us through sensationalist news reports, circulating at the time.

You see, around the 1720s, in the Austrian village of Meduegna (now present day Serbia), a man named Arnold Paole claimed publically to have been bitten by a vampire. The attack had allegedly occurred some years prior, and Paole claimed he had staved off the Vampire’s curse by eating dirt from its grave and smearing himself with its blood. But in 1725, Arnold fell from a haywagon and died from a broken neck. Within several days, others in the village claimed Arnold was haunting them. These people all allegedly died shortly after.

Forty days later, the villagers, now increasingly concerned, dug up Arnold’s grave. They found his corpse showing no signs of decomposition. There seemed to be fluid still running through his veins. His clothing and funeral shroud were also soaked with blood. Numerous other signs led them to believe Paole had become a vampire. The story goes that they drove a stake through his heart, causing his corpse to shriek and scream, before cutting off his head and burning his body. After, they dug up his alleged victims and repeated the process.

Five years later went by, and similar mysterious deaths began to plague the same community, causing them to believe that Arnold was somehow enacting his revenge. It was at this point, that a massive investigation was undertaken to corroborate these events. It was reported on by Johannes Fluckinger, a military surgeon, before making its way across the continent, fascinating everyone from scientists and philosophers to commoners as well.

The reports of Arnold Paole's alleged vampirism, coupled with the Graveyard Poets’ explorations into mortality and the sublime, created a fertile ground for the emergence of Gothic Horror. As new writers interwove themes of death and introspection with folklore and “modern” society, a new literary focus began to come into focus. These works examined the eerie space between modern human experience and the ancient macabre. Complemented by the Romantic movement, which cautioned against the abandonment of past superstitions; these tales often focused on ancestral secrets and how the forbidden things of our past, if ignored, might come back to destroy us…

“Awe and Horror”

Before we jump into the Gothic though, we first need to outline a specific philosophical element crucial to its expression. The element I’m referring to is…

The Sublime.

So what is the “Sublime?” And why is it so important?

The sublime is yet another gift from the Romantic movement. Rooted in aesthetics and philosophy, it refers to a particular emotion common in art and horror. The Sublime is in essence, an overwhelming sense of beauty and terror. It provokes awe and fear in its subject. It is an emotion that is reserved for extraordinary experiences - those that transcend the normal world. Often it is linked to the vastness of nature, or the supernatural and uncanny. This concept crops up regularly in Gothic Horror, manifesting through landscapes and themes that inspire appreciation and dread. Think desolate crumbling castles, dense, dark forests, stormy oceans and encounters with the unknown…

In short, the sublime affords us moments in which we scream: “Oh wow!” and then after: “Oh shit!”

“Foul Secrets Lie Beneath…”

By 1764, Horace Walpole’s classic novel The Castle of Otranto arrives on the literary scene. Telling the story of a cursed prince and his family, it explores themes of fate, guilt, and the supernatural, introducing a new set of modular storytelling blocks for future authors to play with: The haunted castle, mysterious ancestral portraits, tragic family secrets, and supernatural apparitions among others find traction here, and become staples of the genre.

Then, in 1794, Mysteries of Udolpho by Anne Radcliffe is published. Radcliffe’s novel, which places an emphasis on the female experience, tells the story of Emily St. Aubert, as she deals with both terror and romantic intrigue. Like The Castle of Otranto, it too adds building blocks to the Gothic Horror canon, introducing desolate landscapes, vulnerable heroines, and psychological suspense.

After this, we have The Monk in 1795 by Mathew Lewis, which builds on both Walpole and Radcliffe’s work by blending horror elements with eroticism, challenging the moral and societal norms of its time.

These three works, when looked at together, really provide the framework for this stage in horror’s history: settings that explore the sublime, shameful secrets, supernatural hauntings, vulnerable heroines, and a pervasive sense of sex and often, sexual “perversions” for their times.

“Sleeping With Ghosts”

In 1816, due largely to the continued influence of the Romantic tradition, we get what is perhaps the most important moment in all of horror history. A moment told, and retold, fictionalized, and elaborated upon hundreds of times since. I’m speaking oc course, about the Gothic Sleepover that took place that year at Lake Geneva in Switzerland.

I’ll let its most famous attendant, Mary Shelley explain:

“In the summer of 1816, we visited Switzerland, and became the neighbours of Lord Byron. At first we spent our pleasant hours on the lake, or wandering on its shores; and Lord Byron, who was writing the third canto of Childe Harold, was the only one among us who put his thoughts upon paper… …But it proved a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house. Some volumes of ghost stories, translated from the German into French, fell into our hands…

"…We will each write a ghost story," said Lord Byron; and his proposition was acceded to. There were four of us.”

("Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus (Revised edition, 1831)/Introduction - Wikisource, the free online library,")

And so who else was in attendance? Asides from Mary, we have her husband, Percy Shelley, their friend Lord Byron, and Byron’s travelling Physician, Doctor John Polidori.

“I busied myself to think of a story,—a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name. I thought and pondered—vainly. I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.”

("Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus (Revised edition, 1831)/Introduction - Wikisource, the free online library,")

As Mary Shelley pained herself trying to find an idea, the others were already busy with their own. During that rainy summer, Byron wrote a part of a novel he’d never finish, involving an aristocratic hero encountering elements of future vampire fiction. Percy, wrote part of a poem called A Fragment of a Ghost Story, as well as part of a story called The Assassins. Polidori, inspired by the vampire novel Byron quickly abandoned, wrote The Vampyre, a crucial first step in introducing the blood-sucking villain into western literature.

This ghost story competition between the friends is made even more intriguing by the popular theory that they were consuming Laudanum the entire time, possibly helping them in their creative process.

While Polidori’s The Vampyre is an important text, it’s really Mary’s novel - Frankenstein that stands above the rest. In it, Mary explores themes of creation, science, and the sublime. Her story focuses on the ethical implications of playing God and the responsibilities of the creator towards his creation. Now considered a cornerstone of Gothic Horror, Frankenstein is also frequently mentioned as one of the first works of science fiction, and the beginning of the Sci-Fi Horror sub-genre. We’ll save Sci-Fi Horror for another time. For now, it’s enough to recognize Frankenstein as a literary milestone that perfectly reflected the anxieties of its time. In an era marked by rapid scientific advancements and profound questions about humanity's place in the world, Shelley invites readers to ponder the consequences of unchecked ambition and the pursuit of knowledge. These themes still resonate strongly today.

“Nevermore! Nevermore!”

Meanwhile across the pond, the United States was having its own Gothic moment. Largely through the works of one Edgar Allan Poe, the American Gothic tradition begins to flourish in the 19th century, heavily influenced by the writers discussed above. This subgenre took the classic tropes of European Gothic Horror and reshaped them to the American landscape. Poe, who’s works tended to explore the darker aspects of the human psyche, pulled the U.S. into the Gothic game in 1833, with his work MS. Found In A Bottle. This was a short story written in the form of a manuscript found in a bottle at sea. It details the harrowing adventures of an unnamed narrator, who after being shipwrecked, encounters several unexplained phenomena as he tries to get home. MS. Found in a Bottle is an exciting piece because it is maybe one of the first to explore themes of madness, isolation, and existential dread. Core components of later authors like HP Lovecraft, and writers of Weird Fiction and Cosmic Horror.

“Same Fears, Darker Days…”

Gothic Horror would continue on, expanding and developing further, but we’ll leave it here as we move onto Gaslight Horror and the Penny Dreadful. But before we do so, it’s important to note that even though the Gothic utilized many new and refreshing ideas, it still clearly connects back to those classic fears of Antiquity we discussed in essay one.

If you remember, these were:

Mortality and the Undead,

Monsters as explanations for real evil,

Moral instruction and warnings of eternal damnation.

Stories like Frankenstein reveal how Gothic horror reframes the age-old concerns around death. In Frankenstein, Victor Frankenstein’s ambition to create life, ultimately leads him to confront his own mortality. Similarly, Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher draws a connection between madness, isolation and psychological torment with destined death.

When it comes to monsters as explanations for real world evil, Gothic horror introduces a new dimension to its bestiary of creatures. Whilst the Greek myths of the Minotaur and Medusa suggested ways in which monsters might also be victims, and Dante’s Inferno hints at the Devil as something to be pitied, Gothic horror took these ideas and ran with them. The development of the Byronic character archetype - a tragic, dark anti-hero figure - allowed for villains to appear as complex and sometimes sympathetic characters. These antagonists could not only act as scapegoats (like in the past) but also embody the more morally ambiguous and abstract aspects of humanity. Through this interpretation, we get classics like Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, Dorian Gray, and The Phantom of the Opera, among others.

Moral instruction and warnings of damnation are also rife here, with stories like The Monk demonstrating the consequences of submitting to one’s sinful desires. Whilst written in a new era where the Church had significantly less sway, it seems people were still concerned about the potential threat of eternal hellfire.

“There’s A Devil Out There, Haunting These Streets…”

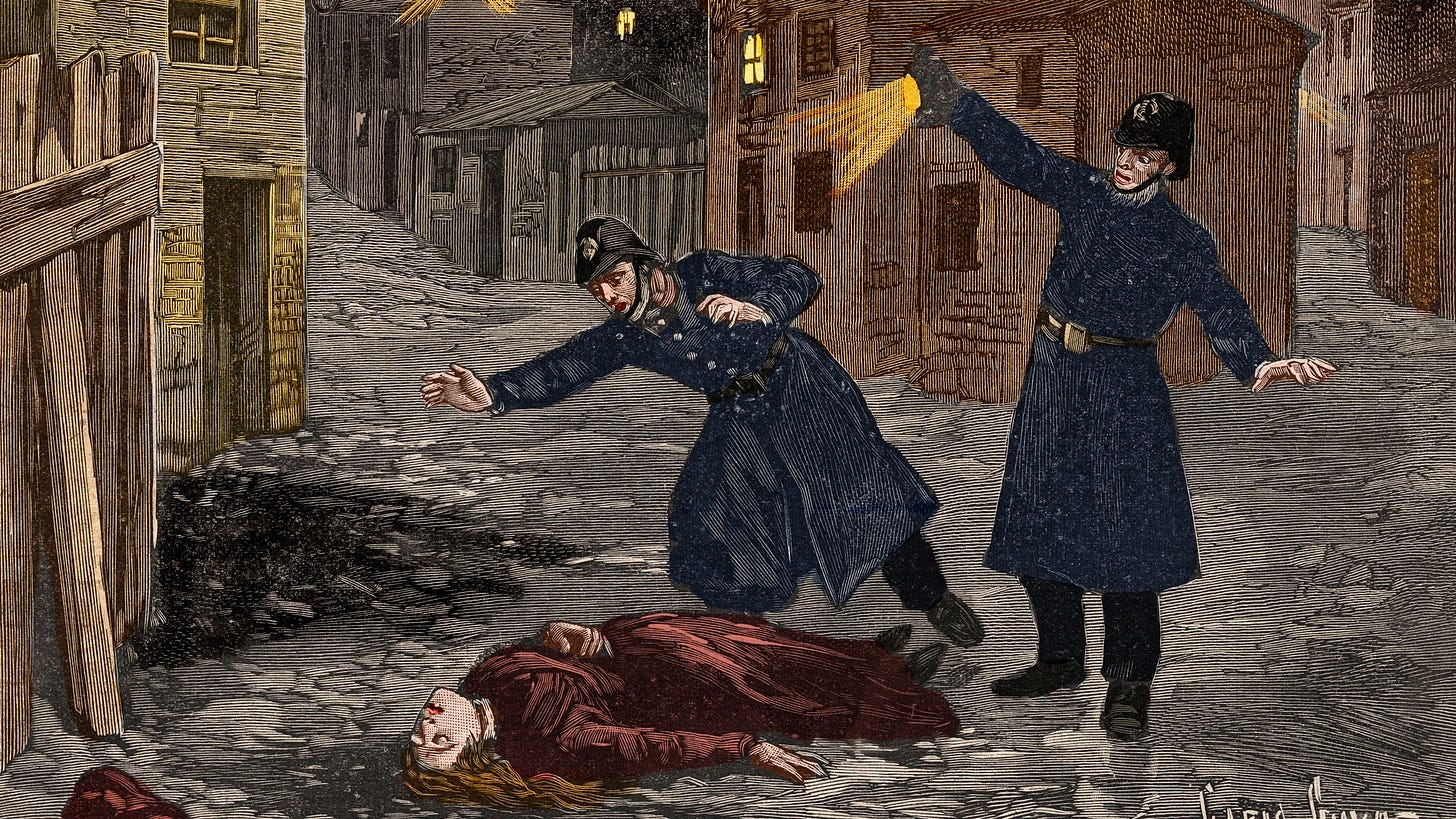

Moving away from the Gothic, we next get Gaslight Horror and the famed Penny Dreadfuls. Beginning in the late 19th Century, Gaslight Horror lifts the themes, archetypes and ideas of the Gothic and relocates them to heavily urbanized settings. Brought on by the industrial age and terrifying real-world evils like the serial killings of Jack The Ripper, Gaslight Horror aimed its sights on social anxieties around the rapid changes in living conditions, overpopulation, class struggles, and urban crime.

Key texts in this subgenre are:

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson,

The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes,

The String of Pearls likely by James Malcom Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest,

The Mysteries of London by George W. M. Reynolds, Thomas Miller and Edward L. Blanchard, and…

Varney The Vampire by James Malcom Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest.

These popular stories often appeared in the form of the Penny Dreadful - cheap booklets that could be purchased for a penny, usually containing stories of crime, horror, and mystery. The affordability of these booklets led to a boom for horror, as they tapped into the salacious nature of urban crime, often muddling real-events with the fictional, and inventing classic horror villains like Sweeney Todd, Mr Hyde, and Spring-Heeled Jack.

Though they eventually fell out of popularity as books became easier to obtain, one can argue that Penny Dreadfuls are what really pulled the genre into the mainstream. Easy to purchase, exciting and easy to read, they acted as a step away from the more “lofty” ambitions of high-brow literature. Penny Dreadfuls also contributed significantly to the rise of Pulp Magazines (covered in the next essay), as well as comic books.

Like Gothic Horror, folklore and mythology, Gaslight Horror continued to express fears of the undead, utilize monsters to explain the unexplainable, and present moral warnings to its readers against sin.

As authors voiced their anxieties about the industrial age and urban life, they unwittingly set the stage for horror’s next development. Our growing understanding of science, medicine and technology, meant that storytellers started to turn away from the evils perpetrated by the spiritual world, and instead, towards an agnostic understanding of human evil and theories of what monstrosities lay in the stars above that science might soon uncover.

In our next essay, we’ll track this change by looking at the works now described as Cosmic Horror and Weird Fiction. In these pieces, the boundaries of the human mind are poked and prodded at, as our universe is revealed to be both devoid of God and teeming with an infinite multitude of incomprehensible terror…

But until then, keep your wooden stakes close and your garlick necklaces on.

Happy Halloween!

Nick

References

A night-piece on death. (2011, May 26). The Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44841/a-night-piece-on-death

Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus (Revised edition, 1831)/Introduction - Wikisource, the free online library. (n.d.). Wikisource, the free library. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Frankenstein,_or_the_Modern_Prometheus_(Revised_Edition,_1831)/Introduction