Video games have produced many iconic villains over the years, but a closer look reveals that many of them lack intentionality. Too often, we rely on cliche or scattered approaches, and while this can work, it’s more like buying a lottery ticket and hoping to have the winning numbers. The good news however is that as game designers, we can train our storytelling muscles. By being more precise, more intentional with our narrative designs, we can strengthen and evolve our villains from being stock-standard characters to figures of unique terror and authority in our story worlds.

But why is this important, and how exactly can we achieve it?

Good Bad-Guys And Why We Need ‘Em

If you jump on Google and scan the internet for the best villains in fiction, you’'ll turn up a few results that appear time and time again. And when we analyse these characters through a narrative design lens, we see some striking commonalities. We learn that in successful stories, villains are rarely ever the end-all-be-all. Rather, many of them are victims themselves. Products of a broken system - be it sociopolitical, spiritual or otherwise.

It would seem, based off the evidence, that good bad-guys are symptoms of a greater issue. They are rarely the issue itself.

A good villain is more than an antagonistic force or a challenge to be overcome. In fact, in many ways, your villain is as important as your protagonist (or player character.) They are more than just somebody who’s wickedness shines a light on the protagonist’s altruistic traits.

In this two-parter, I’m going to unpack what I mean. In this essay, we will discuss three villain archetypes I’ve identified in my career as a Narrative Designer. Archetypes that I call the Unholy Trinity. These Archetypes, when understood and utilized correctly, will strengthen your narratives and create truly satisfying conflicts between the forces of light and dark.

In the next essay, we’ll dive even deeper into how these archetypes interact with players and explore how exactly we can craft truly memorable narrative payoffs.

Those Which Already Exist

A moment ago, I mentioned this concept that good villains are not standalone bastions of evil. Rather, they are products of larger, corrupt and broken systems. When we consider some of the best nasties in video games and other media, we can clearly see this factor at play.

Sephiroth for example, is one of video game history’s most iconic shit-bags. He’s powerful, arrogant and has aspirations to be a god. And yet, even he is the result of something larger than his own darkness. Sephiroth, as we find out is the result of the Shinra Corporation’s unethical exploitation of science and nature. Sephiroth is revealed to be a weaponized superhuman, driven mad by the consequences of corporate greed and genetic manipulation.

Or lets look at Cersei Lannister from Game of Thrones. A beautifully written villain that had myself, and countless others rooting for her one moment, then demanding her head on a silver platter the next. Cersei though, is the inevitable product of Westeros’ feudal system. A societal structure where dynastic power struggles, misogyny, and a corrupt nobility drive her to embrace ruthless methods in order to survive and protect her family.

What about Andrew Ryan, founder of the underwater city of Rapture in the acclaimed video game BioShock? Whilst Andrew is presented to us as an insidious evil, even he is a product. Andrew is the inevitable outcome of extreme capitalist and libertarian ideas. He is a man whose ruthless pursuit of individualism and free-market ideology turned him into a tyrant, ruling over a crumbling and decaying dystopia of madness.

We could go on and on with these kinds of examples. Let me know a few of your favourites. How would you describe them in relation to their own broken systems?

But why does this fact matter? Well, by viewing villains in this way, we afford ourselves as writers and developers, a few exciting avenues to explore.

First, through this framework, we can add deeper levels of sub-text to our stories - commenting on and criticizing the broken systems of our own world, inciting our audiences towards positive change.

The second, is that this framework creates space within the narrative for long-form continuation. By which I mean: if our villains are the products of broken systems, then removing them is not really a solution. It is the system itself that has to be defeated. Simply taking out the villain, only delays the inevitable - eventually another, possibly worse monster will rise to take the place of the first.

Can everybody say franchise potential? While I would argue that ultimately for a good story to work, it does eventually need to come to a satisfying end. Us audiences need our emotional catharsis! Usually, we’ll want to fix those broken systems - however, we can leave them broken for a little while, in order for it to keep pumping out exciting new enemies that our heroes can face.

Lastly, this framework creates space for us to add extra existential threats to the narrative - ticking time bombs that represent the end results of characters (not writers) perpetuating their broken systems for too long. Think: The White Walkers in Game of Thrones, and the evermarching threat of an endless winter. In the HBO series, these are ticking time bombs, acting as prophetic warnings of what will happen if the Lords and Ladies of Westeros are unable to get over their differences and unite against a common threat.

The Unholy Trinity

Examining villains like these, it becomes clear that there are a whole range of archetypal figures we can choose from. However, out of this range, there are three that seem to reign supreme. Three that seem to have an unbreakable grip on our collective imaginations…

Archetype 1: Evil Incarnate

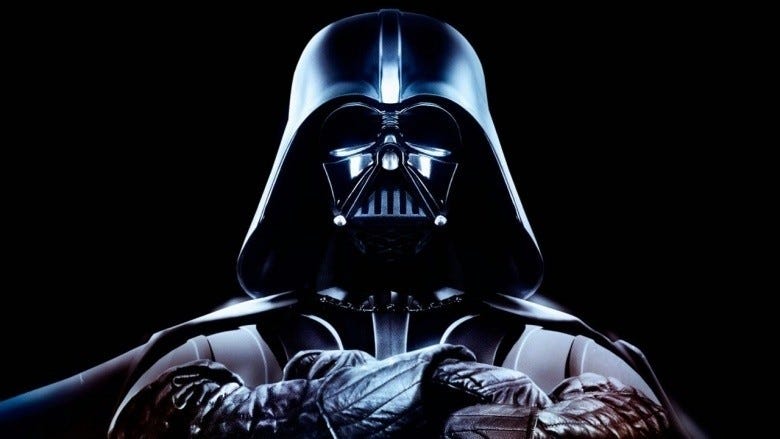

The Evil Incarnate villain represents a primal, almost instinctive kind of darkness. Characters like Darth Vader, or the Dark Lord Sauron operate as forces of pure evil, devoid in most ways of humanizing qualities. Their presence in a story taps into ancient fears and drives audiences and players to seek catharsis through their defeat.

While they may have once begun their lives good, they are now less than human. They have sacrificed themselves and the things they loved long ago, to become hosts of darkness.

These villains tend to have a high body count, but their kills are rarely personal; they are more akin to a force of nature. They tend to be highly melodramatic, and can exist almost entirely off-screen as an “ultimate evil.” Alternatively, they might be more like our favourite slasher movie killers - faceless and/or voiceless, allowing us as players and audience members to superimpose our own anxieties directly upon them.

Ultimately, these villains exist because in the moment in which they are brought low, defeated and/or killed, we as audiences and players are gifted with a powerful sense of satisfaction. Because we love to see the cosmic forces of good triumph over the cosmic forces of evil. For an audience member or player, the death of this kind of character taps into a spiritual or religious component within our lizard-brains - it is the setting right of what was once wrong in the universe.

Archetype 2: The Mad-Man

While the Evil Incarnate archetype dominates through brute force, the Mad-Man acts through unpredictability. Often motivated by a fractured mind, their actions tend to lack rationality, creating a sense of chaos and fear in other characters and the audience or player. They tend to be living contradictions, declaring noble (at least in their eyes) purposes from out their mouths, whilst simultaneously executing innocents with the gun or sword in their hand.

They are typically outsiders to society and often feel misunderstood. Yet they usually only have themselves to blame. They can be highly manipulative and charismatic, but use fear and cruelty as their weapons of choice. They may lay claim to divine revelation or secret knowledge, as a way to justify their actions.

The Mad-Man tends to have a high body-count, and while each kill is personal in the sense that they take time to do it themselves, they also kill indiscriminately simply to make a point. They are typically prone to narcissism or pride. The Mad-Man can be defeated by playing off their personality defects.

Usually, their origin stories are ignored, barely explained, or shown to be gratuitously traumatic. Their origin stories act as microcosms of their behaviour in the present day.

This character exists to provide an enjoyable level of tension for your audience, as well as a high degree of spectacle. We enjoy them because of their unpredictability.

Unlike the Evil Incarnate archetype, our desire to see this character destroyed is driven by blood-lust. The Mad-Man tends to die horribly and ironically, prompting audience cheers. They are sacrifical calfs on the proverbial altar of fiction. The Mad Man has violated the sacred social contract we all agree to, thus their defeat is equal parts punishment and course correction. They die to quench our rage at injustice - even if they themselves are the victims of it too. Their ends serve the continuation of the status quo.

Archetype 3: The Morally Complex Villain

The Complex Villain archetype tends to defy simplistic categorization. Unlike other antagonists, they are more multi-faceted, their motivations rooted in personal traumas, ethical dilemmas and complex world views. Whereas the Evil Incarnate and the Mad-Man archetypes trigger base emotions in audiences and players, the Morally Complex Villain triggers abstract and ambiguous ones.

They are often the most interesting to watch, and the easiest to feel conflicted about. But they are also harder to write well. They rely on a complicated cocktail of empathy, and disgust. They tend to be people who are relatable. Figures we can step into the shoes of, and understand why they make the choices that they do.

Morally Complex Villains have a detailed backstories. Ones that paint them as normal people made victims of fate, or at the very least, abnormal circumstances. Their backstories show us how they got to be where they are, revealing a tragic inevitability.

When we look at the morally complex villain, we are provoked to recognize ourselves. We ask ourselves: If we had walked their path, experienced the things they experienced, would we have turned out any different? In this, the survival of these villains up to that point can even be seen as inspirational. A testimoy to their defiance and strength of will.

To be clear, these characters are not good people, but their agendas are understandable. It is their methods that we take issue with. Like the Mad-Man they can be intelligent, charismatic and unpredictable. Unlike the Mad-Man they don’t typically have an unreliable mind. Instead, their chaos comes from their playing their cards close to their chest.

These characters tend to have smaller personal body counts. They are picky about when to get their hands dirty. But they also have the highest impersonal body counts - usually because they order others to commit atrocities for them. They are efficient and unafraid of taking risks, moving boldly when they need to against their enemies. They can occassionally be cruel, believing that cruelty is a means to an end.

Lastly, the sacrifice of others ultimately comes easy to them. They might outwardly struggle over such a decision, but it is performative - deep down, they know that they were always going to make that choice. They betray friends, lovers and even family members, to move closer to their goal. As audience members and players, we flip-flop between loving and hating them.

When these villains are defeated - if they are defeated - they provoke both satisfaction and sadness in audiences and players. We tend to be glad that they’ve been foiled, but we might also feel for them, mourn for the loss of their dreams, or the fact that they never got to recognize the error of their ways. As narrative designs, they represent all of us - our good bits and bad bits, our complexities and contradictions. The Morally Complex Villain is a safe way for us to confront that truth and pull it apart for revelation.

Forces of Darkness, UNITE!

Understanding archetypes, like the ones we’ve explored in this essay, opens up exciting possibilities in storytelling across all mediums. Once you know how these archetypes function, you can really begin to play with them. As with many elements of narrative design, archetypes are best seen as guidelines rather than rigid rules. Mastery comes with learning how to use them - and then daring to remix them as your confidence grows.

Of course, remixing archetypes isn’t always straightforward. Star Wars for example, has had mixed results in this area. Particularly, we could point to the results of their attempts to shift Darth Vader from being an Evil Incarnate Archetype towards being more of a Morally Complex Villain Archetype in the prequel films. But it can be done. Griffith from the manga Berserk is a strong example of a villain who successfully embodies aspects of the Evil Incarnate Archetype and the Morally Complex Villain Archetype, illustrating how effective blending can work. But witha ll these sorts of thngs, it takes practice, experimentation, and the willingness to make adjustments along the way.

So, as we close up this essay, I encourage you: play with these archetypes! Experiment with switching traits, removing or adding elements, and seeing what works best for your story. At the same time, aim to master the basics. The better you understand these fundamental roles and the emotional functions they serve, the stronger your storytelling craft will become.

Till next time,

Nick.