In her seminal essay, Putting the Gay in Games, Adrienne Shaw presents several alarming statistics about the video game industry. She writes:

“Statistically, the video game industry is fairly homogeneous. According to data from IGDA’s 2005 survey of workforce diversity […] the vast majority (91%) of respondents identify as heterosexual, 5.1% as gay, lesbian or bisexual, and 3.2% declined to answer. Males accounted for 89.1% of those surveyed and 1.5% of all respondents identify as transgendered.” (Shaw, 2009, p.234)

With over 90% of industry workers identifying as heterosexual and 89% as male, it’s no wonder the industry struggles with representation. The lack of LGBTQI+ characters in AAA studio games and the fetishization of women in unrealistic battle armour found in many fantasy titles, contribute to the perception of video games as the domain of pimply fourteen-year-old boys.

More recent statistics show us that the industry continues to grapple with issues of diversity and representation, despite some signs of progress. According to the latest Developer Satisfaction Survey (DSS) conducted by the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) in 2023, approximately 79% of respondents identified as white, while about 31% identified as women - an increase from previous years, though still showing underrepresentation of women and people of color ("IGDA and western University release 2023 developer satisfaction survey," 2024).

Interestingly, the survey indicated that 85% of respondents felt that diversity in the workplace and in game content was important, which reflects a growing awareness and desire for change within the industry. This sentiment has seen a slight increase from prior years, indicating that there is recognition of the need for more inclusive practices. However, the actual implementation of effective diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies appear to lag behind these aspirations, with a notable 28% of workplaces reportedly lacking any EDI programs.

Furtherrmore, hitorical data shows that while awareness and acknowledgement of diversity issues are increasing, the workforce demographics remain relatively stagnant. For instance, in 2005, about 91% of industry professionals indentified as heterosexual, and in 2017, this figure was still quite similar, with 81% identifying as heterosexual. This indicates that while the conversation around diversity is expanding, real change in representation is slow to materialize.

To sum up, while there is a growing recognition of the importance of diversity within games, challenges remain in transforming this understanding into actionable change. There also appears to be a danger of stagnation; developers may mistakenly believe that change has occurred when it has not. Adding to all this, is the uncomfortable truth is that a small, but vocal subsection within the gaming public has positioned itself as being loudly against “wokeness” and “Politics” in games. Such people have commandeered affirmative action tactics like doxing and review bombing in an attempt to force queer developers and their stories back into the closet. This resistance has been notably amplified by movements like Gamergate, which aimed to silence marginalized voices in the industry. While there is growing awareness and dialogue around diversity, systemic challenges persist, such as ingrained cultural attitudes and the impact of harassment that continues to deter many from participating in game development.

Girl “Ghettos” and Gaymers

Now that we’ve examined the statistics, let’s focus specifically on LGBTQI+ representation. Shaw raises a crucial point about the pitfalls game developers face when attempting to create diverse content. As an example, she discusses the industry’s efforts to target the female gaming market:

“Recognizing both the social and economic importance of targeting female gamers, some companies have attempted to court the “girl gamer” market. Market research by companies such as Purple Moon, sought to establish essential qualities of the “girl games market” by looking at how boys and girls play outside of gaming (Gorriz & Medina, 2000, p. 47) Significantly, they did not look at what girls who were already gamers did or did not enjoy but rather were targeting the nongaming girl market. According to Gansmo et al. (2003), when female players are discussed by designers, generally a very traditional feminine stereotype is evoked, which translates into game designs built around social relations, romance, emotions and roleplaying […] Creating a subgenre of games that appeals to stereotypes of gendered play habits resulted in “ghettoization” or girl games…” (Shaw, 2009, p. 233) Emphasis added.

This approach is a blatantly sexist mistake by ?developers? A similar error threatens to repeat itself with queer representation. Shaw illustrates this with an example where Sony took out an advertisement in the gay magazine Attitude to promote the once incredibly popular, now rarely mentioned Singstar. The advert featured half-naked muscular firemen in an attempt to sell the game to gay men. Shaw notes that this approach mirrors the failed strategy used to market games for girls, focusing on flamboyant stereotypes of gay culture rather than recognizing queer gamers as individuals who simply enjjoy video games (Shaw, 2009, p. 238).

The fundamental error in both cases lies in assuming a connection between female gamers and traditional femininity, and between queer gamers and the flamboyant, hypersexualized stereotypes of gay culture. While these stereotypes exist, they do not define every queer person, nor do they encompass the full range of interests and identities among gamers.

Orcs and Issues of Whiteness

Next, let’s explore the representation of PoC in video games through the lens of whiteness in the fantasy genre. In her book Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness Helen Young discusses the implications of Orcs in relation to racial issues:

“Orcs in Fantasy came into existence through Tolkien’s imagination and have been transplanted into countless worlds outside Middle-Earth. In Middle-Earth they are a monstrous Other, constructed through racial discourses. They are: somatically different to the White Self of the fellowship; part of a millennium old Western cultural discourse that Others the East and its people; and the embodiment of racial logics and stereotypes, and the perceived threat of miscegenation. They are the prototypes for the massed armies of evil’s foot-soldiers which swarm the worlds of High Fantasy under different names.” (Young, 2016, p. 89)

Young notes that Orcs are coded to be non-specifically non-White, whereas humans and other humanoid creatures like dwarves and elves are often specifically coded as White. The development of Orcs often incorporates discourses associated specifically with Black culture and/or Native American cultures or other indigenous backgrounds. Young also considers how Orcs are made to be “other” through their skin color (typically green, brown or black), extreme aggression, irrationality, and having a primitive disorganized culture, or a homeland which lies outside the borders of civilization. This problematic portrayal extends to representing PoC and LGBTQI+ characters in fantasy, regardless of their species (Young, 2016, p. 89).

Writing Queer Characters Into Your Games

As a gay Narrative Designer in the industry, I have been vocal about the need for representation in games. In a 2017 interview, I ws asked why it is important for queer audiences to see themselves represented in games and media. To that question, I explained that representation is important (especially for younger queer audiences) because it instills confidence, normalizes queerness, and provides encouragment through portraying queer individuals as heroes instead of monsters of tragic victims.

When creating characters for my stories I strive for complexity, ensuring they embody the full range of human experience - from the good all the way to the bad. My goal is not to create a “gay game” or “LGBTQI+ Fiction,” but rather works that are meant for everyone, that just so happen to feature queer characters in engaging and relatable ways.

In one of the earlier games I worked on - OrbusVR - two central characters, Lord Oscar Hulthine and Lord Markos Rῠnval are both gay and heroic Knights. Markos’ darker skin also allowed for the exploration of post-colonial themes regarding his origins from a colonized country.

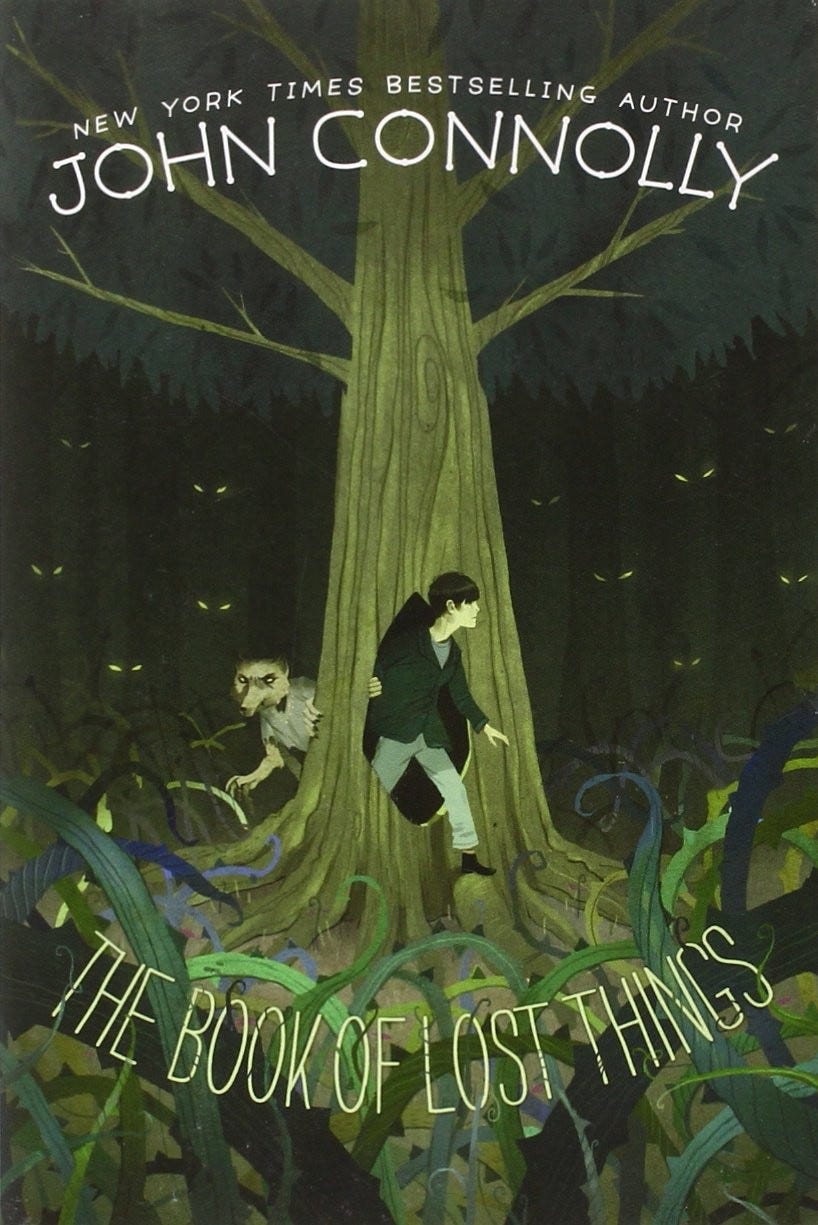

When I was a kid, I read The Book of Lost Things by John Connolly. In it, the protagonist befriends a Knight named Roland, who seeks his lost love, Raphael. Though Connolly never explicitly states Roland is gay, I found inspiration in his chivalrous character. Connolly later mentioned that while he didn’t write Roland as gay, he intentionally left that part of the character ambiguous and open to interpretation (Connolly, 2007).

As a young, closeted gay kid in small town New Zealand, I interpreted the character of Roland through my own lens, and found him to be incredibly inspiring. The ripples of that character still echo through my work today. While Connolly used intentional ambiguity back then, in my own work today, I approach my characters queerness with clarity, without necessarily forcing their sexual identities into the spotlight. I aim to incorporate queerness into dialogue and storytelling, whilst ensuring that such characters are multifaceted people first and sexual being second. In OrbusVR, Oscar and Markos were directly inspired by what I read out of the relationship between Roland and Raphael.

CASE STUDY: ORBUSVR

“It’s you. The thief. You thought you were quiet out there in the Lowland woods, but I have the eyes of a hawk. I saw you disappear into the undergrowth with my crest”

“I took you for a simple villager, a starving peasant who thought they could sell such a treasure so as to fill their hungry belly. Who could’ve known you’d rat me out to the Order? It appears I underestimated your desire to please them. I will not make that mistake a second time”

“This indiscretion, this failure won’t deter me. I remain a loyal soldier. A warrior dedicated to the honor of the Knights of Patreayl! My heart beats in time to the thud of our shields against the skulls of our enemies, and my soul, my soul holds true, enraptured by my fearless leader, Markos of Rῠnval!” (Jones, 2017)

In these initial conversations with Oscar, he reveals his allegiance, and ties it specifically to Markos of Rŭneval, who is singled out as his lover through dialogue implication. Here, I sought to establish something thematically similar to what was common in Chivalric literature of antiquity. In examples of that genre, the concept of friendship amongst men is often blurred with that of romantic love. Look at the relationships between Johnathon and David in the Bible, or Achilles and Patroclus, Damon and Pythias, Oresetes and Pylades in Greek mythology.

After seeing Oscar captured and shipped off to Guild City to be executed, the player is asked to attend to Oscar’s final rights, sparking a conversation that layers further queer subtext upon the character:

“Ha! My little defeater! I didn’t expect to see you in such a place as this… Ah, and is that an Enforcer cloak? So now I understand. Ambition was your motivation, and status your reward.”

“All six of my brothers once wore the crest you wear now… Oh, they’ve long since been promoted and killed on far off battlefields. Even I did a brief stint working the same job as you and them. I always wanted to be an academic, but my father wouldn’t stand for it. He sent me to this city… in a way, it was his own undoing. It was through the Order that I discovered the truth, met Markos, and… well… a story for another time perhaps.” (Jones, 2017)

When we reach the event of Oscar’s execution however, the truth finally comes out, bold and proud:

“I stand here, due to die. Convicted not because of the crimes I have committed, but rather, because I stood for freedom! Freedom in the face of a tyrannical Order… and a desolate goddess! If I am to die, then as my last words, I declare my loyalty one final time to the Patreayl Knighthood, they alone stand to curb the tide of this corruption… Father, I am sorry for what I did to you. And to Sir Markos, I declare my undying loyalty, before the eyes of men and gods. I shall serve thee in the next life, if ever I am given the chance… I love you.

…Executioner, do you worst!” (Jones, 2017)

This is the approach I’ve taken for most games I’ve worked on in terms of creating LGBTQI+ representation. Maintaining queer characters front and centre, I build slowly upon their queerness as a revelation alongside the progress of their character in general.

SUMMING UP…

Oscar and Markos exemplify the depth that queer characters can bring to storytelling in video games. By presenting their relationship authentically and with nuance, we challenge the dominant narratives that often sideline or misrepresent LGBTQI+ identities. It is vital for game developers to understand that queer representation is not merely an inclusionary checkbox; it is an opportunity to enrich narratives, broaden perspectives, and foster empathy among players.

As we look to the future, it is essential to advocate for an industry that not only acknowledges the demand for diversity but actively works to create it. This involves recognizing the unique experiences of queer individuals, creating space for those narratives within games, and crafting characters who resonate with a wide audience while remaining true to their identities.

In this journey toward inclusivity, we must remember that every character—regardless of their sexual orientation—should be designed as a fully realized human being, with flaws, virtues, and a story worth telling. By prioritizing authenticity in character development and representation, the gaming industry can create a more vibrant, engaging, and accepting space for all players.

Absolutely phenomenal piece. As a queer person this was such a great read. Thank you.

>With over 90% of industry workers identifying as heterosexual and 89% as male, it’s no wonder the industry struggles with representation.

By most accounts, the percentage of the population that's gay is around 7%. At the time of the study you cited, it sounds like LGBT people were statistically slightly over represented.